|

Unemployment in Saudi Arabia: The

Ethical and Economic Impact of Foreign

Workers on the Middle East Market.

Basel Farhan (1)

Melissa Brevetti (2)

Detola Laditan (3)

(1) M.A. Candidate, Department of

Economics at Morgan State University,

Baltimore, Maryland, United States

(2) Director of Accreditation at Langston

University, Langston, Oklahoma, United

States

(3) MSc., University of Baltimore,

Baltimore, Maryland, United States

Correspondence:

Melissa

Brevetti

Director of

Accreditation at Langston University,

Langston, Oklahoma, United States

Email: brevetti.melissa@gmail.com

Abstract

Despite its vast economic resources,

Saudi Arabia has high unemployment

among its citizens that is ironic

given the large number of overseas

foreign workers. Over the past decade,

Saudi authorities have introduced

a series of policies and programs

aimed at addressing the situation

and these plans deserve greater urgency

in light of current realities of the

global oil market. This manuscript

thus aims to contribute to these efforts.

It examines the unemployment scenario

in Saudi Arabia primarily as it affects

Saudi citizens, to better understand

how foreign contract workers who have

accumulated over the decades, have

influenced the Saudi labor market.

Employment patterns in both the private

and public sectors, particularly as

they affect citizens and non-citizens,

are studied to better assess the recent

efforts aimed at increasing domestic

participation in the labor force.

Key words: Unemployment, Saudi

Arabia, Foreign workers, economics,

employment

Introduction

As a country on the global arena,

Saudi Arabia is primarily known for

two factors: the religion of Islam

and the abundance of crude oil. According

to De Bel Air (2014), "With Islam,

the Kingdom has an ideological and

political influence over 1.6 billion

Muslims, or 23 percent of the world's

population p. 3" In terms of

crude oil, he explains "the Kingdom

has the second largest proven reserves

and is currently the biggest economy

in the Arab world p. 3." Oil

was originally discovered in the kingdom

in the 1930's, but World War II interrupted

activities, and production later ramped

up right after the war and for the

next two decades, oil revenues that

accrued to the kingdom were largely

based off contracts that awarded greater

shares to the oil multinational corporation.

As such, while the country produced

and exported oil, much of the revenues

were accruing to the major oil companies,

then known as the "Seven Sisters,"

and the country remained largely agrarian

and rural.

However, arising from the Arab-Israeli

war of the early seventies, that prompted

Oil Producing Exporting Countries,

OPEC, members, led largely by the

Saudis, to impose an oil embargo on

the United States and a few other

nations viewed as supporting the Israelis,

the global crude oil market underwent

significantly fundamental changes.

With the crippling embargo resulting

in the price of a barrel of oil quadrupling

on the global market and acute shortages

of gasoline across the United States,

Saudi-led OPEC was able to, under

nationalization programs renegotiate

oil licensing contracts that resulted

in the transfer of vast oil and gas

holdings from the multinationals to

State-owned enterprises. By 1976,

virtually every other major producer

in the mid-East, Africa, Asia, and

Latin America had followed nationalizing

at least some of its production garner

a portion of participation or to completely

control the entire industry and employ

the international companies on a contractual

basis (Kobrin, 1985).

With greater control, and skyrocketing

prices, Saudi Arabia and its fellow

OPEC members became awash with an

abundance of oil revenue. This resulted

in the Saudi's embarking on major

development projects that would help

modernize the kingdom. However, to

achieve this, Saudi Arabia had, and

has continued over the decades, to

rely on and primarily utilize the

abundant supply of low-wage South

East Asians that are admitted into

the kingdom as contract workers. While

these workers are ordinarily not considered

immigrants given the kingdom's labor

laws that govern foreign workers,

immigration rates increased from "800

thousand in 1974 to 4.1 million in

1992, and 6.1 million in 2004"

representing "an increase of

80.5% and 52.1% respectively"

(Al-Gabbani; 2009, p.8). As a consequence,

the last forty years have seen a major

transformation in the country based

on its oil wealth. A transformation

described by Reidel (2015) as from

a poor desert to a rich, conservative

monarchy with global power. Writing

of the effects of the new found wealth

in the kingdom, Sayigh (1973), wrote

of abundance that has "permitted

the inflow of a large volume of imports,

both for the expanding consumption

of the population and for the accelerated

development of the environment."

All this happened directly as a result

of the ballooning of state coffers

from the oil boom of the early seventies.

From the 1972 oil income of about

$2.7billion for the sale of 2.1 million

barrels of oil, 1973 saw incomes of

$4.3billion on sales of 2.7million

barrels and then the 1974 bonanza

of close to $28billion for the sale

of 3million barrels of oil (Sayigh,

1973; p.144).

However, despite being considered

a wealthy country based on its vast

oil and gas production capacity, Saudi

Arabia, like many other nations in

the Middle East and North Africa region,

faces enormous challenges resulting

from high unemployment. With citizens

who have, over the decades, become

accustomed to the largesse that petrodollars

allowed the State to dole out in various

welfare schemes, an absence of work

ethics was fostered resulting in the

current situation where Saudi citizens

make up less than half of the overall

labor force.

Extending from the work ethic culture

is the situation where there is a

marked difference between private

and public sectors within the economy.

While the majority of the workers

in the private sector are foreign

contract workers, the majority in

the public sector are native citizens.

In the private sector where ownership

is by predominantly Saudi businessmen,

the overwhelming preference for employees

is importing foreign labor over local

citizens who they often cite with

having bad work ethics. This becomes

a convenient position of local businesses

that certainly have an incentive in

ensuring lower labor costs as they

seek to maximize their profits. In

some cases, private businesses are

paid commissions by the State for

importing workers to carry out tasks

that are of considerable importance

but have few Saudis willing to do

them-such as trash collection. In

the public sector, positions offer

far more generous pay and benefits

and typically have less demanding

schedules than private sector jobs,

which offer less pay and benefits,

and still have longer hours and basically

no labor law protections. As citizenship

requirements exist for most public

sector positions, the government has,

over the decades, rewarded citizens

with positions resulting in an over-padded

civil service.

Generally, we can define employment

as "the number of people who

have a job", and unemployment

as "the number of people who

do not have a job but are looking

for one" (Blanchard & Johnson,

2003; p. 25) or put differently, "unemployment

refers to the share of the labor force

that is without work but available

for and seeking employment" (The

World Bank, 2014). Unemployment rates

not only vary among countries but

also within individual countries and

result from wide-ranging factors.

The global economic crisis of 2008,

for instance, that directly affected

both the financial and housing industries,

resulted in massive lay-offs that

led to high unemployment across the

globe.

This manuscript explores the unemployment

situation in Saudi Arabia primarily

as it affects citizens and non-citizens

and argues that an overabundance of

foreign contract workers, accumulated

over the decades, has significantly

negatively affected the Saudi labor

force and responsible for the unemployment

rate among Saudi citizens. Beginning

with some background information into

the kingdom of Saudi Arabia and establishing

its current unemployment situation;

it attempts to identify some of the

contributing factors to the high rate

of unemployment and discusses some

of the consequences of the unemployment

figures. Going further, it executes

a comparative analysis of both the

private and public sectors with an

emphasis on the employment and unemployment

patterns between citizens and non-citizens

and examines some of the potential

solutions to achieve lower unemployment

levels.

Literature Review

The issue of unemployment in Saudi

Arabia can be described as being a

relatively recent one given the country

has been considered a wealthy nation

with a high per capita income and

citizens enjoy the benefits that come

with wealth. In 1999, the kingdom

began negotiations to join the World

Trade Organization, WTO, and became

a formal member in December 2011.

This has somewhat unveiled the opaqueness

that Saudi Arabia is notorious for

and has created better insights into

the unemployment and poverty situation

in the kingdom (Sullivan, 2012). Much

has been written about the development

deficiencies in the Middle East and

this was best captured in the landmark

Arab Human Development Report released

by the United Nations in 2002 and

aptly titled "Creating Opportunities

for Future Generations." This

comprehensive document encompassing

the Arab World found "deeply

rooted shortcomings" embedded

in these societies and that were adversely

affecting human development. Specific

recommendations made focused on three

key areas: respect for human rights,

female empowerment, and the pursuit

of knowledge as a prerequisite for

development. Also mentioned in the

report was the high youth population

rates in these countries and the attendant

implications of that as the title

of the report clearly suggests. Less

than a decade later, much of the Arab

world erupted in flames largely as

a result of some of the shortcomings

highlighted in the UN report.

While Saudi Arabia was spared much

of the political upheavals that began

in 2011, with minor skirmishes reported

in certain parts of the Eastern Region,

which is home to predominantly Shia

minorities, it has not escaped the

high unemployment rates plaguing the

region-and considered one of the main

underlying causes of the revolutions

(Al-Qudsi, 2005). Despite the huge

oil wealth associated with the kingdom,

there is a high unemployment rate

among Saudi citizens (Fakeeh, 2009;

Fay ad et al., 2012; AlHamad, 2014).

This rate becomes higher when examined

by age and gender. Saudi youth in

the 20-35 age brackets has an unemployment

rate in the mid-thirties (Saudi CDSI,

2013; Al Omran, 2010; De Bel Air,

2014) while women are unemployed at

about 25% (Al-Munajed, 2010; Eldemerdash,

2014).

Inextricably linked to the Saudi unemployment

situation is the presence of millions

of foreign workers in the kingdom

(Alhamad, 2014; De Bel-Air, 2014)

who began flowing in during the mid-1970s

and have continued to do so over the

last four decades resulting in the

current situation where the country

operates a two-tier economic structure

with citizens dominating the private

sector and foreign workers likewise

in the public sector (Al- Sheikh &

Erbas, 2012; Al-Qudsi, 2005; Hertog,

2013; Torofdar & Yunggar, 2012).

In 2005, concerted efforts began to

address the issue of unemployment.

Under the broad theme of Saudiization,

which is aimed at addressing unemployment

primarily by reducing the amount of

foreign workers in the kingdom, the

government has introduced certain

policies and programs in this regard

(Alshanbri, Khalfan & Maqsood,

2014; Al-Omran, 2010; Alfawaz, Hilal

& Alghannam, 2014; Fleischhaker

et al, 2013). These efforts gained

greater urgency following the protests

in the region in 2011 that led to

the toppling of a few governments

as the Saudi royal family recognizes

the implications of a restive unemployed

youth population. Four main policy

thrusts under the program are examined

here based on much of the available

studies carried out on Saudiization

efforts, Nitaqat, Hafiz, KASP and

Gender Issues, and how all these can

ultimately affect Saudi private sector

employment.

Given that most of these programs

are relatively new, available literature

on the subject is somewhat limited.

However, in one study utilizing international

mobility theory to assess the effectiveness

of these policies on wage rates, Alhamad

(2014) found that the deportations

of foreign workers carried out under

Saudiization enforcement led to wage

increases for both Saudi and non-Saudi

workers but cautioned that Saudi productivity

rates could ultimately lead to further

costs. Limiting foreign workers is

also espoused by Al-Omran (2010) who,

also, calls for a longer term view

and reforms in immigrant and residency

status in dealing with foreign workers

who, in some cases are the second

generation, with families having lived

in the kingdom for decades but still

legally considered as foreigners.

In exploring the educational challenges

facing the country, Alfawaz, Hilal

& Alghanam, (2014) examine the

KASP program and conclude that the

best hope of not only solving the

unemployment problem, but also helping

to diversify the Saudi economy and

evolve in the 21st century knowledge-based

globalized economy, is the scholarship

program which has over a hundred thousand

students in undergraduate and graduate

programs in universities and colleges

across the globe.

Furthermore, this view of the education

and training imperative is explored

by Fayad et al. (2012) who also advocate

that over time, the steps being taken

in the area of education and training

will help "mitigate potential

competitiveness pressure" between

nationals and foreign workers. Echoing

the imperative of education reform,

(Alshanbri, Khalfan & Maqsood,

2014), in a study carried out by HR

managers in the private sector to

measure the effectiveness of the Nitaqat

program, found that while some managers

showed concern with regards to the

work ethic of Saudi citizens, the

majority had no problem hiring Saudis

but advocated for better education,

and better work ethic from Saudi workers.

Also important are issues raised by

(Fleischhaker et al, 2013) with regards

to both labor laws and gender issues

as they both relate to the overall

effort to reduce unemployment with

calls for better-codified labor regulations

that apply to all workers irrespective

of nationality as well as dealing

with the issue of females who have

a much larger unemployment rate than

males.

To focus on female employment in the

kingdom, much of the available studies

here focus on the low labor market

participation rate among Saudi women,

which contributes immensely to the

high overall unemployment among Saudi

citizens (Al-Jarf, 1999; Al -Qudsi,

2005; Al-Fakeeh, 2009; Al-Munajed,

2010). In a study on female Saudi

translators, Al-Jarf (1999) found

that as high as 90% of females educated

as translators between 1990 and 1996

were not working in the field despite

the availability of such positions.

Much of the issues around female unemployment

stem from deep cultural traditions

and practices that impose strict conditions

on the conduct of women in public

that invariably affect their employability.

Others like (AlMunajed, 2010; &Rajkhan,

2014), see the low female participation

rate, under 20%, in the national labor

force as an opportunity to be seized

with females representing an untapped

resource that can help catalyze further

development of the private sector

in long-term efforts aimed at diversification

from oil.

While much of the studies carried

out on the Saudiization programs have

tended to agree broadly on the merits

and achievable success of the individual

programs, others have found disapproval

with the overall thrust of Saudiization.

Eldemerdash, (2014) cautions about

the securitization of Saudiization

and sees the Saudi government enforcement

regime under the program, deportations

of foreign workers and criminalization

of Saudi private sector practices,

as misplaced policies that could ultimately

not yield the desired results. Similarly,

De Bel-Air (2014) examined the enforcement

procedures under Saudiization, and

noted the selective deportations among

different foreign nationals with the

resultant effect being that India

with the largest number of foreign

workers in the kingdom saw relatively

small numbers of them deported while

other nations with fewer numbers like

Yemen and Egypt experienced larger

deportations in a manner that suggested

other political considerations were

also at play. Lastly, Al Fakeeh (2009)

takes a rejectionist approach to Saudiization,

arguing the focus on unemployment

is misplaced and ought to actually

be on employability that should take

a longer term view with programs aimed

at making the necessary cultural shifts

needed to bolster the recognition

of a sound education as a prerequisite

for developing the human capital required

for the 21st century knowledge driven

globalized world that Saudi Arabia

operates in.

While much of these studies have focused

on the Saudi unemployment situation

from the assumption of high oil revenues,

the current realities of oil prices

makes it a more compelling case. For

comparison, while a barrel of oil

is selling for under $30 a barrel

in February 2016, February 2015 it

sold for about $50 and in February

2014, it was about $100.

Given these new realities, which have

led to some subsidy adjustments, the

issue of unemployment in Saudi becomes

even more important as the less revenue

the kingdom makes, the more difficult

it becomes for a welfare-oriented

populace.

Country Profile

and Demographic Structure

A United Nations Development Program

(2015) reports the population of Saudi

Arabia at 30 million and with a Human

Development Index, HDI, of 0.836 that

places it 34th globally. According

to Human Development Report 2015,

"the HDI is a summary measure

for assessing long-term progress in

three basic dimensions of human development:

a long and healthy life, access to

knowledge and a decent standard of

living". The kingdom enjoys a

life expectancy of 75 years. Of the

30 million, roughly 10 million or

30% are foreigners, up from 11% in

1974, and the native Saudi population

has grown steadily at roughly 2.3%

per annum for the past two decades

(Fayad, Raissi, Rasmussen & Westelius;

2012, p.21).

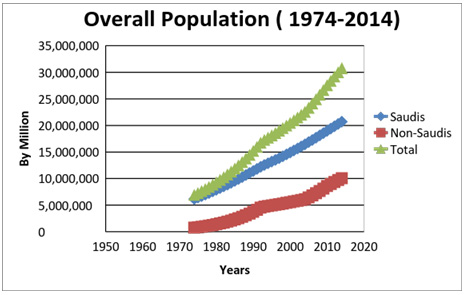

Figure 1: Overall population increase

(2004-2014) by gender and citizenship

status

Source: Central Department of Statistics

& Information

In examining these population figures,

we find a general upward trend in

population growth for both citizens

and non-citizens. Saudi population

has grown from 5 million in 1974 to

roughly 20 million in 2014, a growth

rate of 400% while on the other hand,

the non-Saudi population grew from

roughly 700,000 in 1974 to about 10

million in 2014 representing a growth

of 1429%.

Political System

Founded as a sovereign and independent

nation in 1932, Saudi Arabia operates

an absolute monarchy form of government

in which all power resides in the

hands of a king, aided by members

of the royal family. There is an Allegiance

Council, charged with selecting a

new king. There is also a Council

Of Ministers, drawn from princes and

non-royals that constitute the roughly

30 cabinet office positions, as well

as a 150 person Consultative Assembly

or Shura Council appointed by the

King and charged with making recommendations

on laws but not quite having an actual

law making powers. In 2005, the country

introduced municipal elections to

fill local seats across the country.

Only male citizens who were twenty-one

and older were allowed to participate;

this sparked the movement for female

suffrage.

The next elections scheduled for 2009

were indefinitely postponed and not

held till 2011, also as an all-male

affair and the ensuing female agitations

prompted the then King Abdullah to

give women the right to participate

in the next elections scheduled for

2015. It is important to point out

that in addition to decreeing the

right of women to participate in politics,

the King Abdullah also took the unprecedented

step of appointing women into the

Consultative Assembly. With the death

of King Abdullah in January 2015,

and the ascension of his brother King

Salman, the 2015 election exercise

began in August 2015, and women have

been allowed to register to vote and

to run and hold office, this will

be discussed in the section on gender

issues.

Economic System

According to the kingdom's embassy

in Washington D.C, Saudi Arabia is

the world's largest producer of petroleum,

and has about one-quarter of the world's

oil reserves - over 260 billion barrels.

A year after it was established in

1932, the Kingdom's founder, King

Abdul Aziz Al Saud granted a prospecting

license to an American oil company

SOCAL, which later changed to Chevron.

Oil exports, which began in 1939,

were disrupted by the Second World

War and resumed at its conclusion.

During the 1970s and 1980s, the oil

boom dramatically affected the country,

and it became an economic giant as

a consequence of both an increase

in oil prices as well as the discoveries

of vast quantities of reserves (Royal

Embassy of Saudi Arabia, Washington

DC; 2014). Based on these enormous

discoveries, the country embarked

upon a massive infrastructural expansion

and modernization project that brought

vast growth and development to the

country.

This massive inflow of petrodollars

made Saudi Arabia one of the fastest

growing economies of the time. Indeed,

Saudi Arabia sits atop approximately

25% of the world's petroleum reserves,

and this accordingly makes it the

largest exporter of oil with an average

daily production of 10 million barrels

and installed capacity that can allow

it to ramp up to 14 million barrels.

On the global competitiveness ranking,

Saudi Arabia scored 5.06 out of 7,

making it 24th out of 148 countries.

GDP is $748.4billion allowing for

a Per Capita Income of roughly $26,000.

The oil production levels, furthermore,

have enabled Saudi Arabia, to be the

dominant member of the Organization

of the Petroleum Exporting Countries,

OPEC, which critics describe as a

cartel with dominant control over

the global oil markets. This largely

allowed the country to push its economic

weight around the globe and it is

considered to be a wealthy nation.

Past statistical figures reflect that

the oil sector contributes 45% of

the country's budget and roughly 90%

of export earnings, and this is most

surprising due to the country's "unworkable

desert territory; it consists of very

few commercial ports; very low vegetation

and fresh water resources, limited

farming activity and very little individual

activity beyond that which the production

of oil demands" (Deaver, 2013,

p.110).

In attempting to understand this Saudi

high unemployment effect, Fakeeh asserts,

"Saudi benefited from a large

influx of petrodollars during the

last half of the twentieth century;

there was no indigenous domestic social

structure to provide the people with

skills necessary for building a modern

state" (p 20). Specifically,

Fakkeh notes Saudi Arabia's wealth,

unlike those of over wealthy economies

like Taiwan and South Korea, which

all grew because of the production

and export of manufactured goods,

Saudi's wealth relies on the export

of oil as their only single natural

resource, "which its exploration

required imported expertise and few

local workers" (p. 29). This

would have the effect of further consolidating

the powers of the state given how

oil rents funded state operations

and giving the little need for taxation

revenues that could help engender

public accountability if citizens

feel they have a contributing stake

in state affairs.

Unemployment

in the Saudi Labor Market

To better understand the Saudi economy,

let us examine the labor force between

private and public sectors of the

country. This is also significant

due to large numbers of immigrants

in the country. The Saudi economy,

to a large degree, is built on the

availability of cheap, mainly foreign,

immigrant workers. According to the

2014 Saudi Department of Statistics

and Information figures, (CDSI), Saudi

had an overall labor force of 11,912,209,

the total number of employed persons

in the country was 11,229,865 or 94%,

and the remaining number of 682,344

or roughly 6% represented the unemployed.

Further, broken down by gender, total

male employed stood at about 87% while

total female employed was roughly

13%. On the unemployment side, total

male unemployed was about 40%while

total female unemployed made up the

large chunk of 60%.

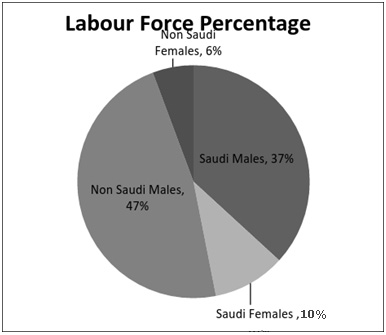

Regarding overall Saudi and non-Saudi

citizens in the labor force, of Saudi

workers employed, male and female

make up 4,944,709 while unemployed

Saudi citizens, male and female, were

646,854. Figure 2 below shows that

while Saudi's make up about 47% of

the labor force, immigrant workers

make up the other 53%. In other words,

there are more foreign immigrant workers

employed than are Saudi citizens.

In the next sections, we take a closer

look at how this immigrant worker

phenomenon affects the public and

private sectors.

Figure 2: Saudi Labor force - Saudi

and non-Saudis

Source: Central Department of Statistics

& Information

Dual Figures-Saudi Unemployment

v non-Saudi unemployment: In

examining figures relating to unemployment

in Saudi Arabia, one often finds different

numbers. One the one hand, most international

organizations, such as the World Bank,

IMF, UN, and others, indicate figures

in the 5-6% range. However, looking

at the economy from within, as well

as making a distinction between Saudis

and non-Saudis, which is the case

with Saudi financial and economic

institutions, Ministry of Labor, CDSI,

the figure is different and always

much higher amongst Saudis (11.7%

in 2014) than non-Saudis (0.3% in

2014). Averaged out, it is close to

6%. This interesting dimension to

the Saudi unemployment issue is as

a result of the vast numbers of foreign

workers who play an enormously substantial

role in the Saudi economy and, as

such, equally significantly impact

unemployment figures. As earlier stated,

foreign workers in the kingdom are

not admitted as immigrants and all

are contracted with fixed-term work

permits. As a result of this, these

foreign workers are essentially in

the country based on a guarantee of

employment, and this explains the

extremely low unemployment rate among

foreign workers in the kingdom, compared

to actual citizens.

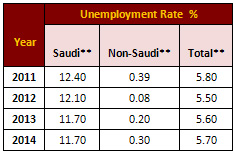

As figure 3 below shows, in every

year from 1999 to 2014, there are

vastly significant differences in

unemployment rates between Saudis

and non-Saudis if we look at five-year

intervals, we find that in 1999, while

Saudis had a rate of 8.1 %, non-Saudis

had 0.84%; by 2004, Saudis had 11%,

non-Saudis 0.8%; five years later

in 2009, Saudis dropped to 10.5%,

but non-Saudis also dropped to 0.3%;

and in 2014, unemployment rose amongst

Saudis to 11.7%, but remained at the

2009 level of 0.3% for non-Saudis.

Understanding

the Foreign Worker Impact on Saudi

Unemployment

The Saudi Public Sector

Like in most developing economies,

employment with the government agencies

in Saudi Arabia comes as a result

of various factors centered primarily

on citizenship rights and then secondarily

on professional or technical expertise.

Essentially, only native Saudis are

generally employed by the government

into the civil service and foreigners

with advanced skill sets like engineers,

doctors, and other professionals can

be employed by the government based

on the unavailability of citizens

to fill such jobs. It is also important

to note that the work ethics of Saudis

play a contributing role to the overall

unemployment figures in the nation.

Seghayer (2013) explains that younger

Saudis typically lack a true commitment

to their jobs and do not seem to demonstrate

professional habits, in addition to

being often absent from work. Moreover,

these Saudis prefer to work in the

public sector, largely based on a

combination of the generous compensation

received lax work requirements and

a guarantee of employment given the

cumbersome process of firing a citizen

from the civil service. Given the

country's resource endowment, the

state can use the civil service as

the main conduit to channel oil income

to the citizens, and this has helped

create a 'huge welfare state' (Al-Sheikh

& Nuri-Erbas, 2012; p.7). This

has, over the decades resulted in

"over-manning and disguised unemployment"

as a result of "the expansion

of employment in the public sector

to absorb Saudi employees" (Mahdi

& Barrientos, 2003; p.75).

In 2005, of the roughly 800,000 employed

in the public sector, including health,

education, judiciary, and other civil

service positions, 91% were Saudi

citizens and ten years later in 2014,

of the total figure of about 1.2 million,

94% were Saudi citizens. This shows

a consistent pattern in which mainly

citizens are employed by the state

and can be expected to remain so as

efforts continue to open up the private

sector to citizens and reduce foreign

workers. Additionally, we also find

an interesting pattern with regards

to gender in the public sector employment

market. With Saudi citizens employed

in the public sector over the ten-year

period, Saudi males were generally

double the Saudi female population

every single year while amongst non-Saudis

on the other hand; the male-female

ratio was more generally balanced

over the decade and with some years

having more females than males. This

can be understood within the context

of 'gender issues' discussed above

in section 2, and the total population

of women working in Saudi is 95 percent

in the public sector (AlMunajed, 2010).

By being allowed to work in government

agencies that can be well regulated

to ensure no gender mingling, the

state can thus provide strong arguments

for increased female labor force participation

and push back against ultra-conservative

teachings that preach against women

working.

The Saudi Private Sector

The private sector, known as Saudi

business owners, generally prefer

to employ foreigners than citizens

for a variety of reasons (Alhamad,

2014; Al Omran, 2010; Hertog, 2013).

In the first instance, as a result

of its exceptional oil productions,

making it a petrostate with large

budgetary expenditures, Saudi Arabia

attracts millions of largely cheap

South East Asian labor, a phenomenon

that began during the oil boom days

of the 1970's that saw Saudi Arabia

embarking on massive development projects

that helped to modernize the kingdom.

This availability of cheap labor over

the decades has created a system in

which private Saudi businesses resist

employing Saudis primarily because

of the easy access to cheap foreign

labor (Al Omran, 2010). In other words,

over the decades, a private sector

business culture has evolved based

on an ever increasing number of available

cheap laborers. Coming from South

East Asian nations like India, Pakistan,

Bangladesh, Thailand, The Philippines,

Indonesia, as well as Arab nations

like Egypt, Sudan, Lebanon, Yemen

and others, these workers make up

an overwhelming majority of workers

employed by private enterprise in

the country (Al Omran, 2010; Summerville

& Sumption, 2010; Edo, 2015).

Based on government policies originally

designed to ensure that shortages

were filled in cases when non-citizens

were unavailable, these have, over

the decades, been broadened and now,

through the use of third party agencies

and other recruiters, private businesses

can import foreign workers on fixed-term

contracts based on renewable short-term

visas. Over the decades, private Saudi

businesses have generated a market

in trading in sponsorship visas, a

practice that has made many middlemen

dealers significant benefits in profits,

and the business community has resisted

different attempts by the government

to curb down on excesses.

When between 2004 and 2005, the government

enacted a 30% reduction in sponsorship

visas issued, the business community

responded by lobbying regulators,

threatening to close businesses and

move to neighboring countries, and

media campaigns aimed at getting the

government to back down which eventually

occurred largely as a result of the

global food crisis of 2007, where

Saudi business interests were able

to use the crisis to justify the continued

need for sponsored foreign labor (AlOmran,

2010). This sponsorship or khafeel

system essentially means that a foreign

worker "needs to be sponsored

by a specific employer and is only

allowed into the country if he has

a sponsor" (Al Omran, 2010; p.22).

Such a worker, upon arrival in the

Kingdom, is allowed to work only for

the sponsor unless permission is given

by the sponsor to transfer the worker's

services to another sponsor. In other

words, workers can be freely traded

among sponsors, and these foreign

laborers are essentially at the mercy

of their bosses and can be fired and

deported anytime. Also, these workers

often "suffer from social abuse

and unfair legal protection"

(Alfawaz, Hilal, & Alghanam, 2014;

p.2). Based on the nature of their

contracts and how much controlling

power the sponsors have over them,

foreign workers are not "entitled

to social and political rights"

(De Bel-Air, 2014; p. 3).

International

Labor Conference, 92ND Session, Geneva,

Switzerland. 2004

While much has been written about

the plight of foreign laborers in

the Gulf and Saudi Arabia with regards

to lack of labor unions and the attendant

rights derived from unionization,

especially collective bargaining and

wage protections, Al-Rasheed (2014)

points out that the Saudis lacks that

right. The country, therefore, has

no associations and no trade unions.

In other words, the country has no

organized labor movements and workers'

rights are essentially not recognized

in any formalized manner.

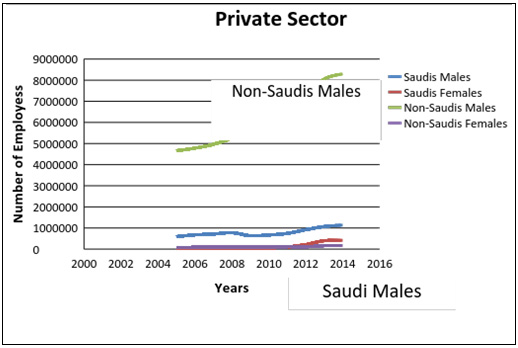

Figure 3: Private sector employment

figures (2005-2014) by gender and

citizenship status

Source: Ministry of Labor

In 2005, out of a total number of

5,400,000 employed in the Saudi private

sector, 4, 740,000 or 87.7% were foreign

workers while Saudi citizens accounted

for only 620,000 or 11.4%. Continuing

with the trend, we find a decade later

in 2014, of a total number of 10,021,339

in the private sector, foreigners

accounted for 8,471,364 or 84.5% while

Saudi citizens accounted for 1,549,975

or 15.4%. One has also to consider

some of the social factors hindering

Saudi nationals from seeking employment

in the private sector. This is important

given that according to Alfawaz, Hilal,

& Alghanam, (2014), the Saudi

social perception of work in the private

sector is struggling due to lower

social status, little job security,

and demand for productivity compared

with the private sector.

In examining private sector employment

from a gender perspective, we find

that non-Saudi males are the most

represented in this sector, and female

Saudi citizens are the least represented.

For example, in 2005, out of an overall

private sector workforce of 5,400,000,

Saudi females accounted for only 0.5%

while non-Saudi males accounted for

86.2%. That same year, Saudi males

accounted for 10.9% while non-Saudi

females were 1.5%. Close to a decade

later, in 2014, and with various intervention

mechanisms in place, we find that

of the total private sector labor

force of 10,021,339, Saudi females

accounted for 4.1%, marking an improvement

in the demographic. Saudi males, on

the other hand, failed to change much

at just about 11.3%. Non-Saudi females

also failed to make much of a change

at 1.6%. The leading category of non-Saudi

males at 82.8% experienced a slight

decline. Here we see that while most

categories experienced slight changes,

the greatest movement was on the part

of Saudi females employed in the private

sector which saw a jump from 0.5%

in 2005 to 4.1% in 2014. In the same

period, non-Saudi male figures fell

from 86.2% in 2005 to 82.8% in 2014

suggesting programs designed to encourage

female employment may be yielding

desired results. It is important to

note that the majority of non-Saudi

female workers in the private sector

are employed as domestic workers.

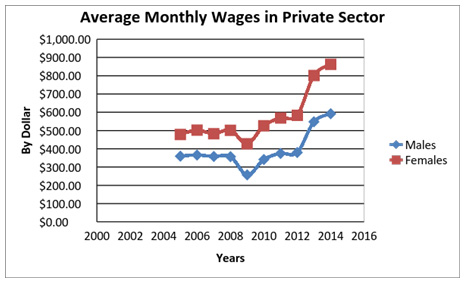

Figure 4: Average Monthly Wages of

Manpower in the Private Sector in

Dollars

Source: Ministry of Labor.

A significant factor impacting the

private sector employment has to do

with wages. In comparison to the public

sector, and unlike other economies,

the public sector not only pays higher

wages, but also guarantees much desired

retirement and other related benefit

packages. Also, both daily and hourly

requirements in both sectors are different

with public sector workers clocking

in, on average, less hours a week

than their private sector counterparts.

While the average salary for Saudi

nationals in the private sector is

about SR3000 ($800), expatriates earn

an average of SR1000 ($270) (Hertog,

2013).

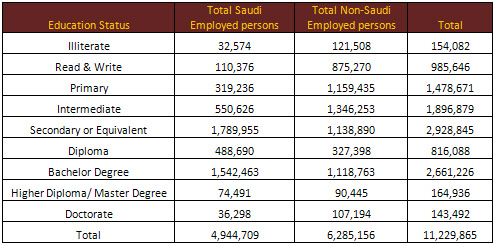

Table 1: Overall employment figures

(15 Year and Above) by education citizenship

status

Source: Central Department of Statistics

& Information

This information allows us to take

a closer look at the educational levels

of Saudis and non-Saudis in the workforce,

and from this analysis, a few pertinent

issues are raised. On all the four

levels of - illiterate, read &

write, primary, and intermediate (which

collectively make up roughly 40% of

the labor force) -foreign workers

significantly outnumber native Saudis.

In the illiterate category of employed

workers, for example, with a total

of 154, 082, Saudis make up 32, 574

or 21% while foreign illiterates make

up 121, 508 or roughly 79%. In the

read and write category, Saudis comprise

of about 11% while foreigners make

up the remaining 89%. Amongst workers

with only primary education, Saudis

are 22%, while foreigners are 78%.

With those at the intermediate level,

Saudis account for 29% while foreigners

are 71%. What we find here is that

in the category of the lowest educated

workers with a total of 4,515,278

out of the overall total of 11,229,865

workers in the labor force, Saudis

make up only 1,012,812 or 22% essentially

meaning there are four times as many

low educated foreign workers in the

country doing jobs that Saudi's could

be doing.

In the next three education levels,

secondary, diploma, and bachelors

which account for 57% of the labor

force, we see a reverse situation

in which Saudi citizens outnumber

foreign workers. When comparing workers

with secondary degrees, 61% are Saudi

and 39% are foreign worker; and while

Saudi diploma holders make up 60%,

foreign workers with diplomas hold

40%; and lastly with bachelor's degree

holders, Saudis account for 58% and

foreigners 42% of those jobs.

This trend becomes reversed again

with foreign workers dominating in

the final two categories of workers

with master's and doctorate degrees

that account for only about 2.7% of

jobs in the entire labor force. Saudis

fare better in employment with master's

degrees with 45% of master's degree

jobs held by Saudis but with doctorates,

foreign workers holding 75% of those

positions.

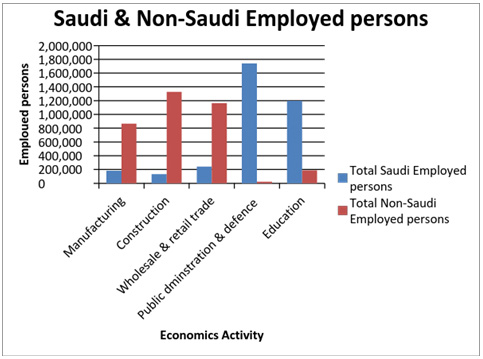

Figure 5: Overall Employed persons

(15 Years and Above) By Economic Activity

and citizenship status

Source: Central Department of Statistics

& Information

This information gives a clearer

picture of the concentrations of citizens

and noncitizens in specific industry

sectors within the overall economy.

This way, interventions designed to

address unemployment can be better

tailored to specific industries.

Of the ten industrial sectors examined,

which include manufacturing, mining

& quarrying, construction, wholesale

& retail, accommodation &

food services, financial & insurance,

professional & scientific, public

demonstration & defense, education,

and domestic workers, only three are

dominated by Saudi citizens while

the remaining seven have more foreign

workers.

Understandably, the industry with

the highest Saudi penetration is public

demonstration and defense, positions

including the armed forces as well

as civil security institutions, which

are reserved for only citizens. Here,

of a total labor force of 1,762,125,

Saudis make up 98%. Conversely, the

industry with the least Saudi's employed

is domestic workers as out of a total

of 966,918 workers, Saudi citizens

make up only 7386 or 0.76%.

In manufacturing, Saudis make up just

17.2%; in construction, 9%; in wholesale

& retail, 17%; in accommodation

& food services, 13%; and in professional/scientific

jobs requiring advanced degrees and

specialization, 19%.

The key take-away from this section

is the stark bifurcation of the Saudi

labor force between the private and

public sectors. The system operates

an over-bloated public sector that

employed 94% of citizens in 2014 and

a private sector dependent on cheap

foreign labor with overseas contract

workers accounting for 85% of its

workforce also in 2014. Saudi authorities

need to seriously tackle issues aimed

at boosting private sector employment

among citizens and this is further

explored in section five which discusses

some of the remedies aimed at reducing

unemployment in the kingdom.

Underlying Causes of Saudi Unemployment

Government Policies on Overseas

Contract Workers

As an absolute monarchy that controls

all aspects of the country, the government

has been directly responsible for

the principles and policies that have

resulted in the country's labor laws

and regulations. The oil increase

of the 1970s and 1980s forced the

government to find foreign labor to

help grow its booming oil industry

because of the severe shortages of

local expertise. With new wealth came

the demand for schools, hospitals,

and other institutions, and since

the locals were not skilled enough

to build and run these establishments,

it became necessary to find foreign

workers. Employers in Saudi found

it easier and less expensive to import

both blue-collar workers and professionals

like teachers, doctors, accountants,

and engineers than to employ locals

who would cost more to train (Lippman,

2012). This policy of imported labor

has resulted in making Saudi Arabia

"one of the world's major destinations

for international migrants, and ranks

5th among the world's top ten countries

with the largest foreign population"

(Al-Gabbani, 2009; p.3).

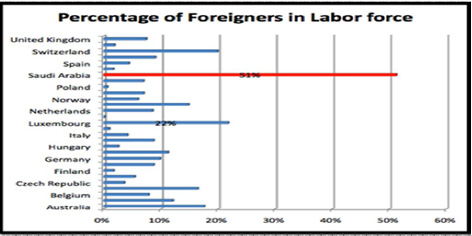

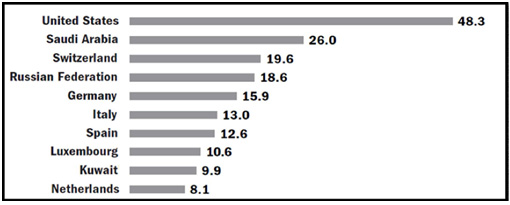

Figure 6 below shows how Saudi

Arabia compares with other Organization

for Economic Cooperation and Development,

OECD, countries regarding foreigners

in the labor force.

Source: Alshanbri, N., Khalfan, M.,

&Maqsood, T. (2014).

In addition to this policy of importing

labor, Saudi government policies also

affected the employment of its citizens

as "prior to 1984, Saudi graduates

were forbidden to be employed in the

private sector and had to work for

the government sector, as they were

financed and sponsored by the government"

(Torofdar&Yunggar 2012). The most

critical challenge of the unemployment

situation is the presence of large

numbers of foreign workers in the

kingdom which began decades ago. As

with other countries which suddenly

become awash with minerals and other

precious commodities, "Saudi

Arabia suffered from the Dutch disease,

which means an increase in the value

of the country's currency with an

increasing dependency on the natural

resources and large inflow of foreign

assistance" (Alfawaz, Hilal,

&Alghannam, 2014). This practice

of importing labor lasted until around

the early 2000s when the Saudi government

began to institute new policies based

on the concept of 'Saudiasation',

which aimed to replace the multinational

workforce with a Saudi workforce in

all workplaces" (Alfawaz, Hilal,

&Alghannam, 2014).As part of efforts

to reduce unemployment among citizens,

the government began a policy aimed

at deporting illegal foreign workers,

and a 2013 amnesty program allowed

4.7 million foreign workers to regularize

their status while another roughly

1 million workers left the kingdom

(De Bel-Air, 2014; p.3).

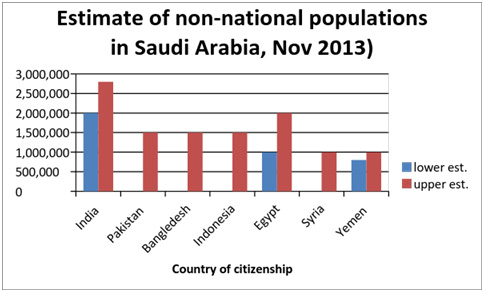

Figure 7: Estimate of non-national

populations in Saudi Arabia, selected

nationalities (Nov 2013)

Source: Demography, Migration and

Labour Markets in Saudi Arabia, Gulf

Labour Markets and Migration, Gulf

Research Center, GLMM - EN - No. 1/2014

Education

Disconnection

The mismatch between the skills required

for economic development and those

actually acquired by students created

a unique problem for the Saudi employment

efforts. Essentially, Saudi students

were not studying the types of majors

required to operate the critical sectors

for national development. Rather than

a focus on science and technology,

there was a concentration in arts,

education and religious studies. Ramadi

(2005) explained that " a very

small percentage of Saudi students

that graduate possess the necessary

scientific and/or technical training

skills needed to meet private-sector

requirements" and as a result,

this impacted "labor nationalization

which has become extremely difficult

to replace skilled foreign workers

with Saudi nationals." Compounding

the situation, the Saudi government

launched a large-scale scholarship

program designed to help in the professional

training of Saudi citizens. With regards

to technical and vocational training,

while the kingdom is home to many

institutions, both privately and publicly

funded, demand still exceeds supply.

Al-Omran (2010) notes the case of

the government-owned Technical &

Vocational Training Corporation, TVTC,

where in 2007, "more than 167

thousand candidates applied for seats

at TVTC, but only 58% were accepted"

(p. 26).

With regards to female education in

trying to understand the Saudi labor

market gender segmentation, AlMunajed

(2010) aptly contends that the "Saudi

educational system simply is not providing

girls with the skills and background

they need to compete successfully

in the labor market" and that

the current system does not "sufficiently

promote analysis, skills development,

problem solving, communication, and

creativity" (p.11).

Culture, Tradition

& Gender Issues

Another underlying factor impacting

high unemployment figures in Saudi

Arabia deals with the societal and

cultural traditions in the Kingdom.

AlMunajed (2010) reminds us that cultural

traditions and local customs play

a "major role in a nation's economic

development, creating a unique set

of opportunities and challenges that

both inform and constrain labor policy"

(p.10). Here, Saudi nationals have

generally looked down on low paying

jobs and have instead sought to bring

in low-skilled workers from other

nations. Other traditional and social

customs, such as males having to act

as guardians for females, affect the

employment situation, and this affects

both sexes. Saudi Arabia's unique

guardianship system ensures that females

are required to have a legal male

guardian and also have to obtain permission

for practically everything they do

given that male guardians are practically

in control of most facets of a woman's

life. As a result, female employment,

as with practically all other endeavors,

is conditioned on being permitted

to seek employment.

In Saudi Arabia, the entire society

is segregated based on gender, and

this also affects employment. As a

result, just as schools and other

institutions are gender separated,

so is the workplace in Saudi Arabia;

it is only recently things are beginning

to change. In the most conservative

quarters of the society, there are

some who don't believe women ought

to be employed at all and should focus

solely on domestic affairs. This gender

factor is a critically important issue

in understanding unemployment in Saudi

Arabia.In examining the 2011 overall

unemployment rate of 12.4 %, we find

that amongst females it was 35% compared

to 7.4% for males (Alhamad, 2014).

Beginning in 2005, with the ascent

to the throne by the late King Abdullah,

several significant changes were made

over the course of the King's reign,

which ended in January 2015, that

were aimed directly at giving women

greater rights and freedoms in the

kingdom. These changes over the years

are noteworthy, as AlMunajed (2010)

asserts that since 1992, women's participation

rate almost tripled from 5.4 percent

to 14.4 percent in 2009. Also in 2009,

the Kingdom recorded a first with

the appointment of a woman as the

deputy education minister, being the

first time a woman would hold a cabinet

position. The government also adopted

policies related to vacation time,

maternity leave, and provision of

nurseries all aimed at encouraging

female participation in the labor

force (Lippman, 2012; Eldemerdash,

2014). In 2012, a royal decree by

the late king granted rights to women

to be appointed to the National Consultative

Assembly or ShuraCouncil, an upper-level

advisory council appointed by the

king that can propose but not pass

or enforce laws, as well as to actually

run as candidates in municipal elections,

and based on this, women joined, for

the first time in the Kingdoms history,

the Consultative Council.It is important

to note that following the introduction

of women in the Council, the following

laws all relating to women's affairs

have been passed by the council and

introduced into governance: Criminalize

Domestic Abuse, passed in 2013; Granting

a law license to first Saudi female

lawyer, January 2014; and the Council's

acceptance to consider a petition

in favor of female driving (Rajkhan,

2014). The crowning glory for Abdullah's

efforts came on December 12, 2015

when Saudi women both stood for and

voted in municipal elections for the

first time in the kingdom's history.

However, despite these improvements,

there is still much to be achieved

in improving the employment situation

for Saudi women. Being the most conservative

of the Gulf Arab States, Saudi still

considerably lags behind other Gulf

Cooperation Council, GCC countries.

In 2009, Bahrain had a national female

participation rate of 34 percent;

Qatar had 36 percent; Kuwait had 43

percent; and the United Arab Emirates,

UAE had 60 percent (AlMunajed, 2010).

Al-Jarf(1999) found that "90%

of female Saudi translators who graduated

between 1990 and 1996 are not working

as translators" and that many

graduates found the available jobs

for women to be "unsuitable because

of working conditions, stringent qualifications,

staff policies, salaries and benefits"

(p. 391). Al-Jarf goes on to note

that based on the strong influence

of culture and traditions, particularly

as they play out within the family

dynamic, many graduates are faced

with meeting requirements meant to

conform to tradition and culture.

Some respondents in the study responded

that "their families forbade

them to work as translators"

while some stated that their families

"did not allow them to work in

the private sector, at hospitals,

embassies and corporations because

of concerns about contact with men

and working hours that might interfere

with family obligations" (p.394).

Consequences

of Unemployment in Saudi Arabia

Potentially Lost Revenues

Based on the huge amount of foreign

workers in the country, in addition

to the unemployment among nationals,

the Kingdom also faces the outflow

of funds that are sent back home by

the foreign workers. As millions of

these workers leave their homes, and

in some cases families, behind, in

search of better economic opportunities,

they often become responsible for

families and relatives back home based

on the wages they earn in the kingdom.

Many of these workers are in the kingdom

doing jobs that a lot of Saudi's based

on some of the cultural norms discussed

above believe socially beneath them.

In 2009, it was estimated that the

labor force stands at 7.337 million,

of which 80% are non-nationals (Cordesman,

2002). It is estimated that over a

ten-year period between 1998 and 2008

some 524 billion (SAR) equaling $139

billion left Saudi Arabia due to foreign

workers sending money to their home

countries, for example, Bangladesh,

Egypt, Pakistan, and the Philippines,

which are major labor exporting countries

(Torofdar&Jobbar; 2012).

Figure 8 below shows the top 10

sources of global remittance payments

($billion) in 2009

Source: Alshanbri, N., Khalfan, M.,

&Maqsood, T. (2014).

Given the current fiscal environment,

the kingdom finds itself with oil

prices continuing to slide, ensuring

that all loopholes are pegged become

a matter of necessity and the government

may want to explore measures aimed

at limiting the wage outflows of foreign

workers.

Social Costs

Besides the obvious economic effects

of high unemployment as well as the

political consequences of periods

of high unemployment on ruling governments,

there are also social costs that need

to be mentioned. Regarding the political

consequences, much has been debated

about the impact of high youth unemployment

as a catalyst for the Arab Spring

uprisings across parts of the Middle

East and North Africa (Hertog, 2013;

Behar & Mok, 2013). With many

nations in the region up in flames,

the late King Abdullah "circumvented

protest in Saudi by announcing a massive

$130 billion subsidy package to fund

new housing programmes, raise the

minimum wage of public servants, (mostly

Saudi's) and create more employment

opportunities in the government sector"

(De Bel-Air, 2014; p.4).

In addition to the potential for high

crime rates and also as a result of

the high youth population in the Kingdom,

Saudi Arabia has to be especially

careful to ensure the idleness of

unemployment does not help foster

larger societal ills. Al Omran (2010),

cautions of the effects of unemployment

on the "psychological state of

the unemployed" such as "low

self-esteem, depression, which lead

to weak family ties and isolation

from the community" (p.16). Substance

abuse is one such area that causes

concern based on how easy unemployment

affects personal esteem and can lead

one to substances. Although not widely

known, drug abuse is also a major

problem for authorities. In October

2015, it was widely reported globally

that a Saudi prince was arrested with

"2 tons of captagon amphetamine

pills" on his private plane in

Beirut Lebanon in an attempt to fly

on to Saudi Arabia (Qiblawi &

Cullinane, 2015).

Another area of concern arising from

unemployment has to do with the effects

of the resulting discontent that comes

with an inability to find a means

of sustenance through employment.

Either as a result of becoming unemployed

via layoffs or not being able to secure

employment upon graduation from formal

training, inability to find work,

particularly in a country like Saudi

Arabia with its vast energy resources,

can lead the unemployed to begin questioning

the systems with political agitation

for better policies, which in turn,

if sustained, can lead to social unrest.

Also of great importance is the potential

for radicalization among the disillusioned,

who in some cases are victims of unemployment

and its general attendant despair.

It is well understood that radical

elements prey on the indigent and

entice them into radicalization based

to a large extent on their economic

conditions with the promises of providing

for them.

Current Options

for Saudi Unemployment

Saudiization Program

To help remedy the high unemployment

situation in the Kingdom, the government

has been instituting some policies

and programs aimed primarily at creating

employment opportunities for millions

of its youth. Most of these programs,

launched in the early 2000s, are centered

around training and positioning the

youth to enable them to take over

from the foreign workers in the country.

At its core, Saudiization seeks three

primary objectives: to increase employment

among citizens; to reduce the reliance

on foreign workers; and to reduce

the amount of remittances foreign

workers send out of the kingdom (Alshanbri,

Khalfan & Maqsood, 2014; Alfawaz,

Hilal, & Alghannam, 2014). Specifically,

the government enacted policies that

restricted the numbers of foreign

workers employed, limited certain

occupations for Saudis only, and required

the private sector to reduce foreign

workers (Eldemerdash, 2014).

Additionally, and in recognition of

the importance of education as the

foundation to building a productive

citizenry, twenty-three universities

were founded in the period (2000-2008)

to boost Saudi Arabia's higher education

capabilities. In 2009, the government

set up the King Abdullah University

of Science and Technology to encourage

research in science, medicine, computer

science, engineering, and education,

with a budget of over 10 billion US

dollars to support its goal to be

one of the leading universities in

the world. In the technical training

industry, the Saudi government also

established seven new technical institutes

for women and 16 vocational training

centers in the period of 2000-2008

(Alshammari, 2009). The government

is aggressively developing a higher

education system that will supply

the engineering and research talent

needed to support advanced technology

and medical industries (Alshammari,

2009). Following the Arab Spring revolts

of January 2011, Saudiization gained

further urgency and the then Saudi

King Abdullah responded with the Royal

Decrees of 2011 ( February 23 and

March 18) that created "unemployment

benefits" as well as "more

aggressive guidelines for Saudiiization"

(Al-Sheikh & Nuri-Erbas, 2012).

King

Abdullah Scholarship Program, KASP

The flagship of the Abdullah Saudiization

efforts is the KASP "which is

considered to be the largest fully

endowed government scholarship program

ever supported by a nation-state"

since launched in 2005/2006, and the

program sponsors "qualified Saudi

students to gain a bachelor, master,

or Ph.D. degree as well as medical

fellowships to the world's best universities"

(Alzabani, 2004). From 2006 to 2012,

an estimation of about"140,000

students have been sponsored"

by the program, and the Saudi Arabian

government has spent about"$5.3

billion to date to cover tuition fees;

life expenses; the students' spouses

and children who live overseas with

the students, and cover the annual

ticket to Saudi Arabia" (Alfawaz,

Hilal, & Alghannam, 2014). This

is an excellent program that is well

suited to help to solve some of the

long-term unemployment issues as well

as other general issues that need

tackling in the Kingdom to help build

a 21st century nation. With such large

numbers of college level citizens

scattered around different institutions

across the globe in pursuit of education,

the kingdom is poised to benefit from

the skills and expertise the scholarship

recipients, who are bound by scholarship

contract terms, to return to the country

upon completion of studies. Additionally,

and equally importantly, these students

serve as cultural ambassadors for

their country both in exporting their

culture, as well as in bringing other

cultures back home.

The Human

Resources Development Fund, HRDF

The HRDF is a government agency designed

to help address unemployment and it

provide grants for qualifying, training,

and recruiting Saudis in the private

sector. Program incentives for employers

to recruit, train, and employ Saudis

include "75% of the salary of

employees while in training (up to

a maximum of 1,500 per month) for

three months, and 50% of the salary

for the first two years (up to 2,000

per month)"and in addition, the

HRDF pays "75% of the training

costs of a Saudi employee in the private

sector for two years" (Alzalabani,

2004).

Hafiz

Program

Launched as part of the Royal Decrees

of 2011, and administered by the HRDF,

Hafiz essentially provides unemployment

benefits to young Saudis who qualify.

It provides "unemployed young

Saudis with a monthly allowance of

SAR 2000 ($533) for one year only

as well as conditional on their participation

in job search and training activities"

(Fleischhaker et. al 2013). In 2014

Al-Obaid completed a study to measure

the effects of Hafiz on beneficiaries'

consumption and ultimately economic

growth, His results found that this

program helped to support and motivate

Saudis who are unemployed and to assist

in building their career skills and

also boost the Saudi Economy by creating

a powerful multiplier effect taking

advantage of the beneficiaries high

consumption tendency" (p.1).

The response to the program has been

overwhelming, and out of the roughly

2 million that applied for the program

in 2012, about 1.3 million qualified,

of which 70% of these were women (Al

Obaid, 2014). Based on the roughly

1.3 million eligible applicants, Hafiz

would be depositing roughly SR 2.7

billion ($720 million) monthly in

beneficiaries accounts (Al Obaid,

2014). It is important to note that

in addition to being a remedy for

high unemployment, Hafiz also allows

for more up-to-date demographic data

management in terms of the overall

labor trends in the kingdom. A major

critique of the program is the extent

to which the unemployment benefits

help stimulate economic growth and

this is a topic that remains controversial.

Following the passage, by the U.S

Congress in 2013, of a law that ended

unemployment benefits at the end of

that year, (Hagedorn, Manovskii, and

Mitman, 2015) found that "a 1%

drop in benefit duration leads to

a statistically significant increase

in employment by 0.0161 log points"

and that "1.8 million additional

jobs were created in 2014 due to the

benefit cut". Another area of

concern has been the effect of unemployment

benefits on inflationary trends.

Alhamad (2014) cautions that when

examining inflation in Saudi Arabia,

"we find that general index figures

can be misleading and do not explain

why people are complaining about higher

prices" but when specific sectors

like housing, water, electricity,

and gas are examined closer, one finds

them much higher than the general

index. In a study for the International

Monetary Fund, IMF, (Shbaikat, 2015)

explains that "expatriates have

helped dampen the inflationary impact

of higher growth during oil cycles

and helped limit real exchange rate

appreciation" and, as such, "inflation

has been low in Saudi Arabia despite

strong growth, and has remained below

that of trading partners" and

this "has limited the appreciation

of the real effective exchange rate".

Nitaqat

Program

This particular program Launched in

June 2011, Nitaqat, which means 'zones'

or 'ranges' in Arabic, is a program

unveiled by the Saudi Ministry of

Labor as part of efforts aimed at

addressing high unemployment (Alshanbri,

Khalfan & Maqsood, 2014). Designed

to build on previous efforts aimed

at indigenizing labor, Nitaqat focuses

primarily on private sector employment

of Saudis but also established a minimum

wage of SR 3000 ($800) for the Saudi

public sector. Under the improved

scheme, private companies are graded

on the four categories of, Premier

Green, Green, Yellow, Red, based upon

their compliance with Nitaqat requirements.

In each category, there are incentives

and sanctions to help improve compliance.

For example, companies with a majority

of foreign workers are fined a fee

of SR 200 ($53) per worker per month,

proceeds of which are funneled back

into the Hafiz unemployment benefit

scheme.

Regarding incentives, the policy also

loosened some of the restrictions

on foreign workers changing employers

freely (Fleischhaker et al., 2013).

Regarding the major provisions, (Crossley,

Taylor, Wardrop & Morrison; 2012)

explain that Nitaqat:

• Delineated 41 economic activities

as operational in the private sector

• Abolished the mandatory 30%

applicable to Saudiization under the

old system

• Issued new percentages that

factored in establishments' capabilities

and citizen availability

• Allowed for firm size to become

the basis for determining Saudiization

percentage

Regarding firm size, companies were

classified based on their number of

employees in the following enumeration:

Huge: 3000+; Large: 500+; Medium:

50-499; Small: 10-49; Very small:

9 or less. In its actual application,

firms with 9 or fewer employees are

generally exempt from the program

but must employ at least one Saudi

citizen.

In all, responses are mixed on the

outcomes of the program. Alhamad (2014)

argues that nitaqat has been successful

in that since its introduction, most

firms were in the red category, meaning

they needed to hire more Saudi workers

to remain operational, and this "caused

both the wage rate and the Saudi labor

force to increase, causing unemployment

to drop" (p.4).

Table 2: Unemployment rate from

2011 to 2014 by citizenship status:

Source: Central Department of Statistics

& Information, Ministry of Economy

and Planning.

Cultural shifts

It is also extremely important to

address the cultural hindrances to

gainful employment particularly with

stereotypes associated with certain

types of jobs. Norms, habits and assumptions

about certain occupations, largely

based on beliefs that Saudis shouldn't

be engaged in jobs considered to be

beneath them, need to be engaged through

well-structured campaigns that promote

the virtues of working hard for one's

nation if efforts towards reducing

unemployment, based on a 'Saudiization'

policy, are to be successful. Accordingly,

this is an area that the authorities

pay a lot of attention to as they

formulate and implement policies since

Saudi Arabia has a speical adherence

to its inherited values. This unemployment

situation, therefore, is a challenge

for the government to provide solutions

without altering or conflicting with

the culture (Alfawaz, Hilal, &Alghannam,

2014).

While much has been said about the

potential benefits of the Saudiization

policies, (Fakeeh, 2009) argues that

the policy falls short as it targets

"the symptom (unemployment) instead

of focusing on the problem employability"

and the focus should be on evolving

an "indigenous domestic social

structure" that can create the

right human capital required to operate

in the 21st century knowledge-based

globalized economy. However, one is

encouraged particularly given the

giant strides achieved regarding greater

female rights in general and also

specifically with current trends in

female employment.

Conclusion

and Discussion

While Saudi Arabia continues to face

challenges both regionally and internationally,

arguably the greatest challenge the

kingdom currently faces is the domestic

reality of how to manage the issue

of high unemployment among citizens,

particularly given its high youth

population.

When the Arab Spring uprisings, of

which strong connections to unemployment

and other socio-economic issues have

been established, broke out in the

region in 2011, the Kingdom was spared

the upheaval largely in part to extremely

generous welfare package rolled out

to placate citizens. However, with

greater costly regional and international

engagement, namely, the wars in Yemen

and Syria, financial and economic

aid in the billions to countries like

Egypt and Lebanon; the headquarters

of a new global Islamic military coalition

designed to address the issue of the

Islamic State, all present substantial

economic challenges to the kingdom

which is reeling from the collapse

of oil prices and further add pressure

to employment initiatives designed

to increase citizens in the labor

force.

Given these urgent realities, this

article examined the realities of

the Saudi private and public sectors

to help explain the concentration

of foreign workers in the private

sector and how this impacts the overall

labor market. The study found that

the Saudi economy operates a two-tier

system with deep structural imbalances

between the private and public sectors.

While nationality requirements help

ensure that citizens are employed

in the public sector with its generous

wages and benefits, they also ensure

foreign workers are sought after for

the much lower wage and little or

non-existent benefits and labor protections

of the jobs in the private sector.

Further examination revealed the concentration

of foreign workers in the private

sector is largely underpinned by a

combination of economic and socio-cultural

factors. Decades of cheap foreign

labor freely flowing into the sector